Your daily tasks online are flowing smoothly, and then suddenly, everything stops. Webpages don’t load, files are unreachable, and customers are upset. It’s a network outage, and the implications are vast, particularly for global networks providers serving thousands.

In this article, we’ll explore the different aspects of network outages, including their types, causes, and effective ways to handle them.

What is a Network Outage?

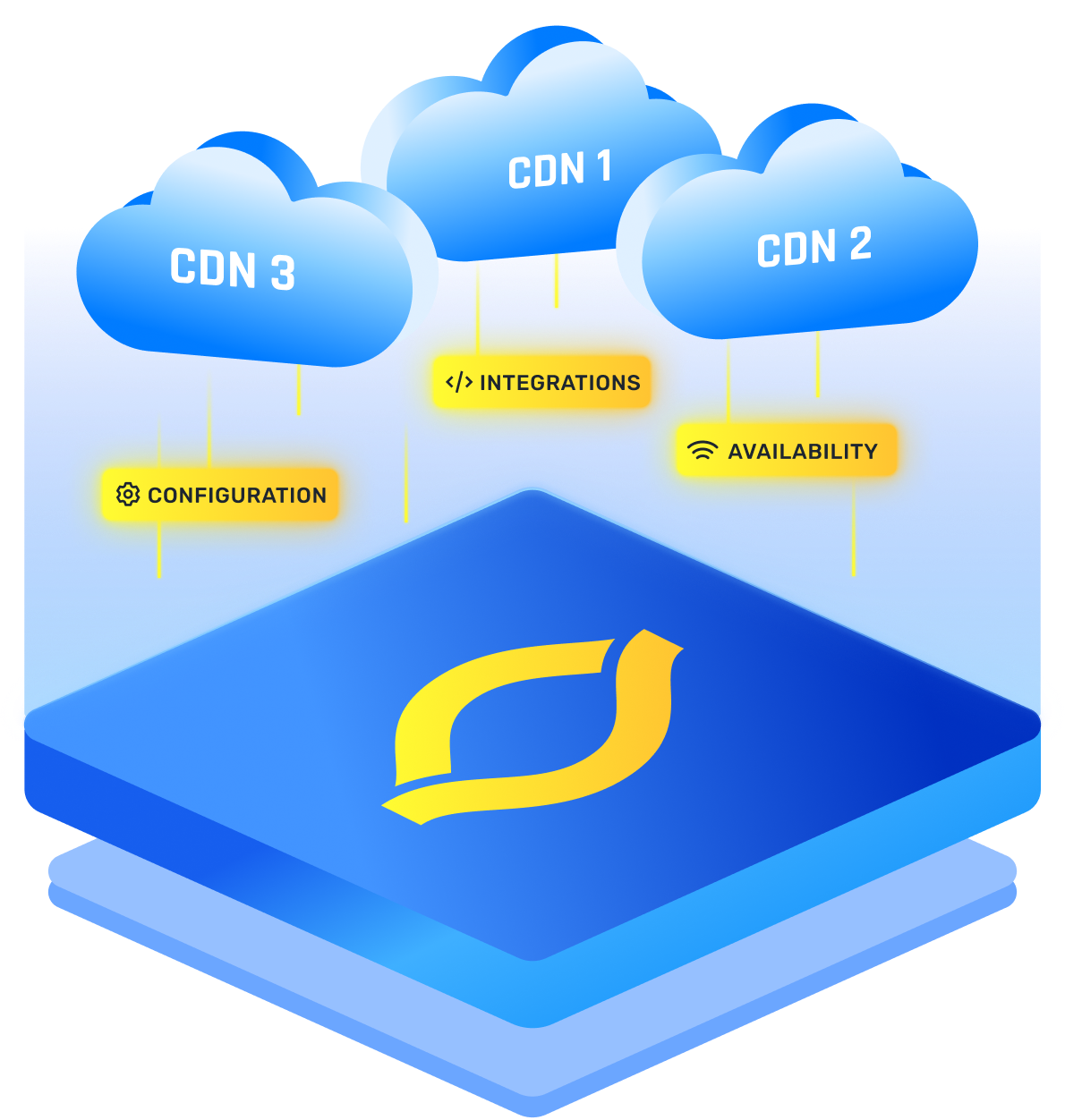

A network outage is a disruption, a halt, a freeze that can immobilize your world in seconds. But when we’re talking about a global network outage of CDN (Content Delivery Network) or a network provider that serves thousands - if not millions of customers, the stakes are even higher.

Imagine a major highway in a bustling city suddenly blocked. The traffic comes to a standstill, creating a ripple effect that affects not just the immediate vicinity but all connected routes and even neighboring cities. A network outage is just like that highway.

CDNs are like the superhighways of the internet, responsible for delivering content to users from nearby servers, optimizing speed, and ensuring a seamless user experience. When these superhighways are blocked, websites load at a snail’s pace or, worse, become completely inaccessible.

{{cool-component}}

Definition

A Global Network Outage refers to the failure or unavailability of the network that distributes content across various geographical locations. This is not a local interruption; it’s a colossal event that can lead to:

It’s a complex issue with multifaceted consequences. It’s a critical challenge with widespread implications for businesses, consumers, and the broader digital economy.

Types of Network Outages

In the vast and interconnected web of a Content Delivery Network (CDN) or a major network provider that serves thousands of customers, an outage can take many forms.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown:

1. Total Outage

A Total network outage means complete inaccessibility. The system is down, and nothing gets through. You’d be surprised to know that a CDN can experience a global outage at least once every 1 to 4 years!

2. Partial Outage

In a partial outage, only certain parts of the network are affected. It might be a particular region, specific services, or a subset of users. Outages like these can occur several times within a year.

3. Latency-Related Outage

Sometimes, the network doesn’t completely fail, but the delays in content delivery might as well render it non-functional.

These are not mere technicalities. They are live, dynamic challenges that CDNs and network providers must wrestle with every day.

The Network Outage Lifecycle (Detection → Containment → Resolution)

Here’s how it goes:

- Detection

Automated monitors (synthetic probes, flow logs, BGP health checks) or user reports trip the first alert. Key metrics: packet loss = 100 %, traffic = 0 TPS, error spikes beyond alert thresholds.

Goal: Recognize the anomaly within seconds. - Containment

Engineers isolate the fault to a device, PoP, or route. Actions may include:

- Dynamically rerouting traffic via BGP or Anycast fail-over.

- Disabling faulty nodes or pulling them from load balancers.

- Activating pre-tested “safe mode” configs.

Goal: Stop the bleed; restore partial service or prevent outage propagation.

- Resolution

Root cause is fixed; hardware swapped, misconfig rolled back, software patched. Traffic is reintroduced gradually while monitoring latency, error-rate, and capacity headroom.

Goal: Return to full functionality and verify stability via post-incident checks.

- Post-incident: Document timelines, conduct a blameless review, and create action items to shorten Detection time or automate future Containment steps.

Known Causes of Network Outages

These causes are more than just glitches. It would be better to think of them as significant roadblocks that can bring a colossal network to its knees.

1. Hardware Failures

Even the most robust systems rely on physical hardware, and hardware can fail.

- Servers: These can overheat or suffer other mechanical failures.

- Routers and Switches: These devices manage the flow of data. A failure here can stop traffic entirely.

2. Software Bugs and Errors

Software drives the modern network, and bugs or unexpected errors in the code can literally cause havoc.

- Operating System: Flaws here can lead to instability or total failure.

3. Human Error

There’s a reason companies hesitate to hand production builds in an intern's hands. Humans design, build, and manage networks, and they can make mistakes.

- Misconfiguration: Incorrect configuration can lead to inefficiencies or failures.

- Accidental Shutdown: Accidental commands can lead to unintentional shutdowns or complete restarts.

4. Natural Disasters

Mother Nature can wreak havoc on the best-laid plans.

- Earthquakes: Can damage physical infrastructure.

- Floods: Can inundate data centers or other vital equipment.

5. Overloads and Capacity Issues

More traffic than the system can handle leads to overloads.

- Traffic Surges: Unexpected spikes in traffic can overwhelm systems.

- Insufficient Bandwidth: Without enough bandwidth, data transmission slows or stops.

Network Outage vs. Brownout

- A network outage is a total failure; traffic stops, services drop, and users see hard errors.

- A brownout is partial degradation; packets squeak through but performance is so poor it feels broken.

Distinguishing them guides triage and stakeholder messaging.

Rule of thumb: If users experience complete unavailability, treat it as an outage; if they endure extreme slowness or sporadic failures, classify it as a brownout and throttle response accordingly.

Best Practices to Handle Network Outage

These best practices, when implemented effectively, create a resilient network that can withstand the challenges of serving thousands of customers on a global scale.

Remember, the goal is to achieve the “Five Nines” uptime which refers to a system's availability 99.999% of the time. It's a gold standard in the industry, translating to just over 5 minutes of downtime per year

1. Implementing an Active-Active Policy

An Active-Active policy involves running multiple instances of a service simultaneously. It ensures that if one part fails, the others continue to function.

2. Investing in Backup and Disaster Recovery

When all else fails, having robust backup and disaster recovery plans can save the day. However, it’s not really recommended since backup and disaster recovery methods are not taken care of as frequently as the main infrastructure.

You can think of them as an old car in your garage that hasn’t been started in the past 15 years. By the time you’d need it, there’s no guarantee if it’ll run or not.

Conclusion

In a world where the digital highway never sleeps, and where thousands of customers rely on uninterrupted service, there’s no room for complacency. It’s a dynamic, challenging environment that demands nothing but the best.

After all, it’s not just about keeping the lights on; it’s about illuminating the path forward in a digital world where excellence isn’t just an aspiration but a requirement!

FAQs

1. How does network outage differ from downtime or disruption?

A network outage is complete loss of connectivity; downtime may be planned, and disruption is degraded performance. Rapid tools that continuously check for network outages are essential, whereas planned downtime is announced and managed in advance.

2. How do network outages affect global services like CDNs compared to local networks?

With CDNs, a single fiber cut can trigger a global network outage update, rerouting traffic worldwide; local LAN failures stay isolated. Because CDNs serve billions, even brief internet network outages amplify latency and revenue loss.

3. What are the most common causes of network outages?

Typical network outage causes include router firmware bugs, BGP misconfiguration, DDoS floods, power loss, and human error. Single-point failures in routing, DNS, or transport layers can propagate quickly beyond the original fault domain.

4. How do hardware failures lead to network outages?

Overheated switches, failing power supplies, or severed fiber disrupt packet forwarding, creating cascading timeouts. Hardware sits on the data plane, so redundancy gaps let one board failure escalate into a service-wide outage.

5. What are the best practices for preventing network outages and ensuring high availability?

Use multi-region designs, automated failover, capacity tests, and patch management. Log incidents with a network outage root cause analysis template to capture lessons, and reinforce resilience through continuous monitoring plus chaos drills.

6. How does aiming for 5 Nines availability help minimize the risk of outages?

Targeting 99.999 % uptime demands N+1 redundancy, fast rollbacks, and strict change control. These measures compress MTTR, leaving only about five minutes of potential downtime per year and reducing outage exposure dramatically.

.png)

.png)

.png)